Hito Steyerl

Superhumanity. December 2016

Creative Destruction and Cybernetic History

I saw the future. It was empty.

A clean slate, flat, designed through and through.

In his 1963 film “How to Kill People” designer George Nelson argues that killing is a matter of design, next to fashion and homemaking. Nelson states that design is crucial in improving both the form and function of weapons. It deploys aesthetics to improve lethal technology.

An accelerated version of the design of killing recently went on trial in this city. Its old town was destroyed, expropriated, in parts eradicated. Young locals claiming autonomy started an insurgency. Massive state violence squashed it, claimed buildings, destroyed neighborhoods, strangled movement, hopes for devolution, secularism and equality. Other cities fared worse. Many are dead. Elsewhere, operations were still ongoing. No, this city is not in Syria. Not in Iraq either. Let’s call it the old town for now. Artifacts found in the area date back to the stone age.

The future design of killing is already in action here.

It is accelerationist, articulating soft- and hardwares, combining emergency missives, programs, forms and templates. Tanks are coordinated with databases, chemicals meet excavators, social media come across tear gas, languages, special forces and managed visibility.

In the streets children were playing with a dilapidated computer keyboard thrown out onto a pile of stuff and debris. It said “Fun City” in big red letters. In the twelfth century one of the important predecessors of computer technology and cybernetics had lived in the old town.1 Scholar Al-Jazari devised many automata and pieces of cutting edge engineering. One of his most astonishing designs is a band of musical robots floating on a boat in a lake, serving drinks to guests. Another one of his devices is seen as anticipating the design of programmable machines.2 He wrote the so-called “Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices,” featuring dozens of inventions in the areas of hydropower, medicine, engineering, timekeeping, music and entertainment. Now, the area where these designs were made is being destroyed.

Warfare, construction and destruction literally take place behind screens—under cover—requiring planning and installation. Blueprints were designed. Laws bent and sculpted. Minds both numbed and incited by the media glare of permanent emergency. Troops were deployed as well as architects, TV, checkpoints, internet cuts and bureaucracy. The design of killing orchestrates military, housing and religiously underpinned population policies. It shifts gears across emergency measures, land registers, pimped passions and curated acts of daily harassment and violence. It deploys trolls, fiduciaries, breaking news and calls to prayer. People are rotated in and out of territories, ranked by affinity to the current hegemony. The design of killing is smooth, participatory, progressing and aggressive; supported by irregulars and occasional machete killings. It is strong, brash, striving for purity and danger. It quickly reshuffles both its allies and its enemies. It quashes the dissimilar and dissenting. It is asymmetrical, multidimensional, overwhelming, ruling from a position of aerial supremacy.

After the fighting had ended, the curfew continued. Big white plastic sheets were covering all entrances to the area to block any view of the former combat zones. An army of bulldozers was brought in. Construction became the continuation of warfare with other means. The rubble of the torn down buildings was removed by workers brought in from afar, partly rumored to be dumped into the river, partly stored in highly guarded landfills far from the city center. Parents were said to dig for their missing children´s bodies in secret. They had joined the uprising and were unaccounted for. Some remnants of barricades still remained in the streets, soaked with the smell of dead bodies. Special forces roamed about arresting anyone who seemed to be taking pictures. “You can’t erase them,” said one. “Once you take them they are directly uploaded to the cloud.”

A 3-D render video of reconstruction plans was released while the area was still under curfew. Render ghosts patrol a sort of tidied gamescape built in traditional looking styles, omitting signs of the different cultures and religions that had populated the city since antiquity. Images of destruction are replaced with digital renders of happy playgrounds and Hausmannized walkways by way of misaligned wipes.

The video uses wipes to transition from one state to another, from present to future, from elected municipality to emergency rule,3 from working class neighborhood to prime real-estate. Wipes as a filmic means are a powerful political symbol. They show displacement by erasure, or more precisely, replacement. They clear one image by shoving in another and pushing the old one out of sight. They visually wipe out the initial population, the buildings, elected representatives and property rights to “clear” the space and inhabit it with a more convenient population, more culturally homogenous cityscape, more aligned administration and home-owners. According to the simulation, the void in the old town would be intensified by newly built expensive developments rehashing by-gone templates, rendering the city as a site for consumption, possession and conquest. The objects of this type of design are ultimately the people and, as Brecht said, their deposition (or disposal, if deemed necessary). The wipe is the filmic equivalent of this. The design of killing is a permanent coup against a non-compliant part of people, against resistant human systems and economies.

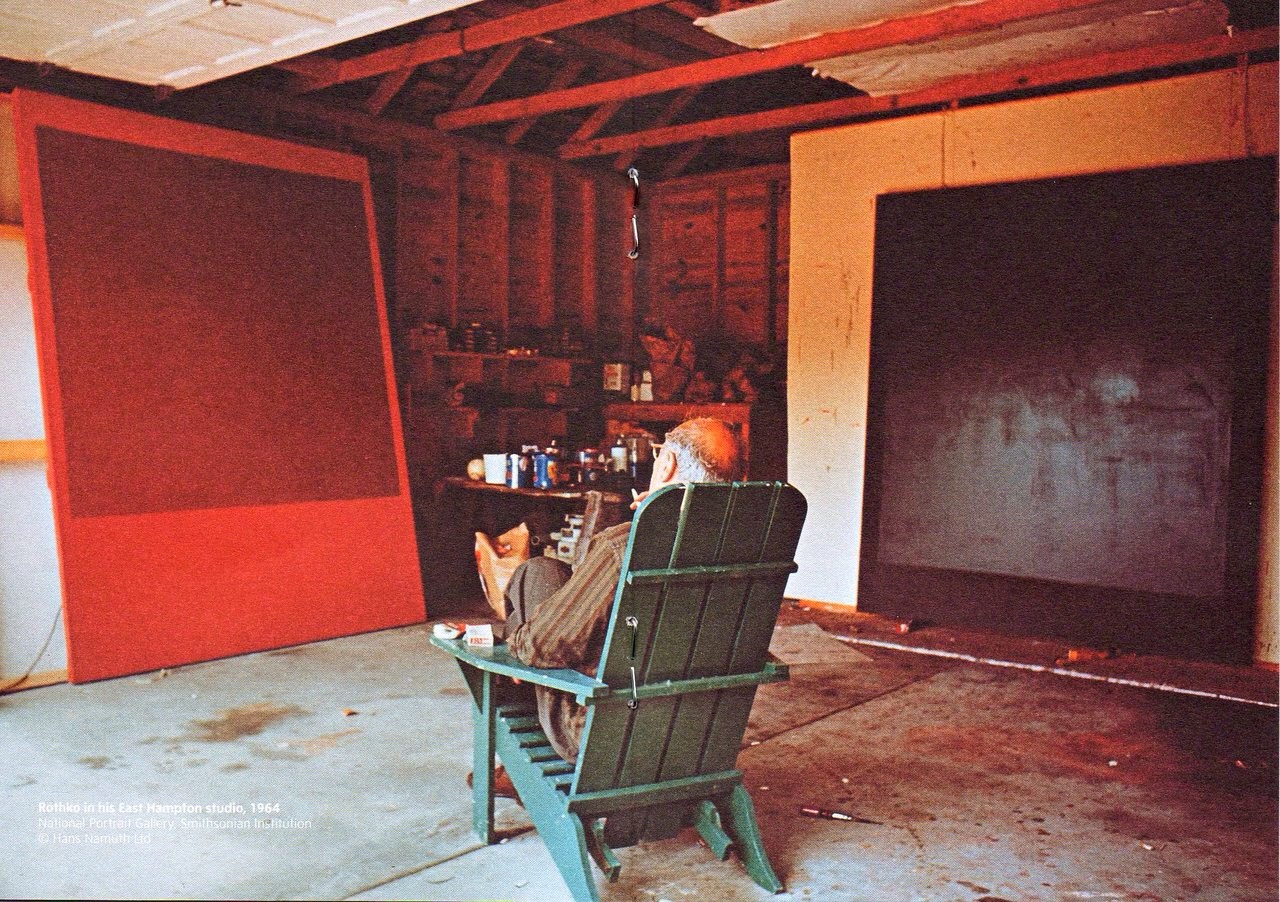

Illustrations from a copy of his Book of Ingenious Mechanical Devices with scratched out and partly erased faces of Al Jazaris musical robots.

So, where is this old town? It is in Turkey, and more precisely Diyarbakır, the unofficial capital of Kurdish populated regions. Worse cases exist all over the region. The interesting thing is not that these events happen. They happen all the time, continuously. The interesting thing is that most people think that they are perfectly normal. Disaffection is part of the overall design structure, as well as the feeling that all of this is too difficult to comprehend and too specific to unravel. Yet this place seems to be designed as a unique case that just follows its own rules, if any. It is not included into the horizon of a shared humanity; it is designed as singular case, a small-scale singularity.4

So let’s take a few steps back to draw more general conclusions. What does this specific instance of the design of killing mean for the idea of design as a whole?

One could think of Martin Heidegger’s notion of the being-toward-death (Dasein zum Tode), the embeddedness of death within life. Similarly, we could talk in this case about “Design zum Tode,” or a type of design in which death is the all-encompassing horizon, founding a structure of meaning that is strictly hierarchical and violent.5

But something else is blatantly apparent as well, and it becomes tangible through the lens of filmic recording. Imagine a bulldozer doing its work recorded on video. It destroys buildings and tears them to the ground. Now imagine the same recording being played backwards. It will show something very peculiar, namely a bulldozer that actually constructs a building. You will see that dust and debris will violently contract into building materials. The structure will materialize as if sucked from thin air with some kind of brutalist vacuum cleaner. In fact, the process you see in this imaginary video played in reverse is very similar to what I described; it is a pristine visualization of a special variety of creative destruction.

Shortly before World War I, sociologist Werner Sombart coined the term “creative destruction” in his book War and Capitalism.6 During World War II, Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter labeled creative destruction “the essential fact about capitalism.”7 Schumpeter drew on Karl Marx´s description of capitalism’s ability to dissolve all sorts of seemingly solid structures and force them to constantly upgrade and renew, both from within and without. Both Marx and writers like David Harvey emphasized that “creative destruction” was still primarily a process of destruction.8 However, the term “creative destruction” became popular within neoliberal ideologies as a sort of necessary internal cleansing process to keep up productivity and efficiency. Its destructivism echoes in both futurism and contemporary accelerationism, both of which celebrate some kind of mandatory catastrophe.

Let me be very clear: these notions of “creative destruction” are by no means adequate to explain what happened in the old town. The situation in this region cannot just be explained in economic terms; nationalism and religion play a role too, not to mention superimposing imperial histories. In one word: it’s complicated. But most people would just zone out if offered a detailed explanation and continue watching cat videos.

Today, the term “creative disruption” seems to have taken the place of creative destruction.9 Automation of blue and white collar labor, artificial intelligence, machine learning, cybernetic control systems or “autonomous” appliances are examples of current so-called disruptive technologies, violently shaking up existing societies, markets and technologies. This is where we circle back to Al-Jazari´s mechanical robots, predecessors of disruptive technologies. Which types of design are associated with “disruptive” technologies, if any? What are social technologies of disruption? How are Twitter bots, trolls, leaks and blanket internet cuts deployed to accelerate autocratic rule? How do contemporary robots cause unemployment, and what about networked commodities and semi-autonomous weapons systems? How about widespread artificial stupidity, dysfunctional systems and endless hotlines from hell? How about the oversized Hyundai and Komatsu cranes and bulldozers, ploughing through destroyed cities, performing an absurd ballet mécanique, punching through ruins, clawing through social fabric, erasing lived presents and eagerly building blazing emptiness?

Disruptive innovation is causing social polarization through the decimation of jobs, mass surveillance and algorithmic confusion. It facilitates the fragmentation of societies by creating anti-social tech monopolies that spread bubbled resentment, change cities, magnify shade and maximize poorly paid freelance work. The effects of these social and technological disruptions include nationalist, sometimes nativist, fascist or ultrareligious mass movements.10 Creative disruption, fueled by automation and cybernetic control, runs in parallel with an age of political fragmentation. The forces of extreme capital, turbocharged with tribal and fundamentalist hatred, reorganize within more narrow entities.

In modernist science fiction, the worst kinds of governments used to be imagined as a single artificial intelligence remote controlling society. However todays real existing proto-and parafascisms rely on decentralized artificial stupidity. Bot armies, like farms and filter bubbles, form the gut brains of political sentiment, manufacturing shitstorms that pose as popular passion. The idea of technocrat fascist rule—supposedly detached, omniscient and sophisticated—is realized as a barrage of dumbed down tweets. Democracy’s demos is replaced by a mob on mobiles11 capturing peoples activities, motion and vital energies. But in contrast to the modernist dystopias, current autocracies do not rely on the perfection of such systems. They rather thrive on their permanent breakdown, dysfunction and so-called “predictive” capacities to create havoc.

Time seems especially affected by disruption. Think back to the reversed bulldozer video: the impression of creative destruction only comes about because time was reversed and is running backwards. After 1989, Jacques Derrida dramatically declared that time was “out of joint” and basically running amok. Writers like Francis Fukuyama thought history somehow petered out. Jean-François Lyotard described the present as a succession of explosion-like shocks, after which nothing in particular happened.12 Simultaneously, logistics reorganized global production chains, trying to montage disparate shreds of times to maximize efficiency and profit. Echoing cut-and-paste aesthetics, the resulting fragmented time created large-scale havoc for people who had to organize their own around increasingly impossible, fractured and often unpaid work hours and schedules.

Added to this is a dimension of time that is no longer accessible to humans, but only to networked so-called control systems that produce flash crashes and high frequency trading scams. Financialization introduces a host of further complications: the economic viability of the present is sustained by debt, that is, by future income claimed, consumed or spent in the present. Thus on the one hand futures are depleted, and on the other, presents are destabilized. In short, the present feels as if it is constituted by emptying out the future to sustain a looping version of a past that never existed. Which means that for at least parts of this trajectory, time indeed runs backwards, from an emptied out future to nurturing a stagnant imaginary past, sustained by disruptive design.

Disruption shows in the jitter in the ill-aligned wipes of the old towns’ 3D render. The transition between present and future is abrupt and literally uneven: frames look as if jolted by earthquakes. In replacing a present urban reality characterized by strong social bonds with a sanitized digital projection that renders population replacement, disruptive design shows grief and dispossession thinly plastered over with an opportunist layer of pixels.

Warfare in the old town is far from being irrelevant, marginal or peripheral, since it shows a singular form of disruptive design, a specific design of killing, a special form of wrecked cutting-edge temporality. Futures are hastened, not by spending future incomes, but by making future deaths happen in the present; a sort of application of the mechanism of debt to that of military control, occupation and expropriation.

While dreaming of the one technological singularity to once-and-for-all render humanity superfluous, disruption as a social, aesthetic and militarized process creates countless little singularities, entities trapped within the horizons of what autocrats declare as their own history, identity, culture, ideology, race or religion; each with their own incompatible rules, or more precisely, their own incompatible lack of rules.13 “Creative disruption” is not just realized by the wrecking of buildings and urban areas. It refers to the wrecking of a horizon of common understanding, replacing it by narrow, parallel, top-down, trimmed and bleached artificial histories.

This is exactly how processes of disruption might affect you, if you live somewhere else that is. Not in the sense that you will necessarily be expropriated, displaced or even worse. This might happen or not, depending on where (and who) you are. But you too might get trapped in your own singular hell of a future repeating invented pasts, with one part of the population hell-bent on getting rid of another. People will peer in from afar, conclude they can’t understand what’s going on, and keep watching cat videos.

What to do about this? What is the opposite design, a type of creation that assists pluriform, horizontal forms of life, and that can be comprehended as part of a shared humanity? What is the contrary to a procedure that inflates, accelerates, purges, disrupts and homogenizes; a process that designs humanity as a uniform, cleansed and allegedly superior product; a superhumanity comprised of sanitized render ghosts?

The contrary is a process that doesn’t grow via destruction, but very literally de-grows constructively. This type of construction is not creating inflation, but devolution. Not centralized competition but cooperative autonomy. Not fragmenting time and dividing people, but reducing expansion, inflation, consumption, debt, disruption, occupation and death. Not superhumanity; humanity as such would perfectly do.

A woman had stayed in the old town on her own throughout the curfew to take care of her cow, who lived in the back stable. Her daughters had climbed through a waterfall in the Roman era walls every week to supply her with basic needs. They kept being shot at by soldiers. This went on for weeks on end. When we talked to her, the cow had just had a baby. One of the team members was a veterinarian.

Daughter: Our calf is sick. Please come and see.

Vet: Sure, what happened? Is it newborn? Did it get the first milk of its mother?

Mum: No, it didn’t get the colostrum. There was no milk. The labor was difficult. It started five times over and stopped again.

Daughter: The other calf reached first and drank all the milk, we didn’t realize it.

Daughter: Mum, where is the calf?

Mum: [calls into the stable] Where is it? My little pistachu, where are you?

Notes

- An overview of Al-Jazaris works: Allah’s Automata Artifacts of the Arab-Islamic Renaissance (800-1200), eds. Siegfried Zielinski and Peter Weibel (Hatje Cantz, 2015); Donald Hill, “Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East,” Scientific American (May 1991), 64–69.

- “A 13th Century Programmable Robot (Archive),” University of Sheffield. http://web.archive.org/web/20070629182810/http://www.shef.ac.uk/marcoms/eview/articles58/robot.html

- The elected municipality of the old town was recently deposed under emergency legislation. Then the mayors of the city were arrested under the suspicion of supporting “terror” alongside dozens of other elected lawmakers, journalists, etc.

- My notion of singularity is based on Peter Hallward’s extremely useful discussion of singular vs. generic situations in Absolutely Postcolonial (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2001) and Frederic Jameson’s extremely useful “Aesthetics of Singularity,” New Left Review 92 (March–April 2015).

- My notion of singularity is based on Peter Hallward’s extremely useful discussion of singular vs. generic situations in Absolutely Postcolonial (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2001) and Frederic Jameson’s extremely useful “Aesthetics of Singularity,” New Left Review 92 (March–April 2015).

- Werner Sombart, Krieg Und Kapitalismus (Munich and Leipzig: Verlag von Duncker & Humblot, 1913).

- ®

- Karl Marx, Grundrisse (1857), trans. Nicolaus, Martin (1973), (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1993), 750.

- Even though it seems to apply to a slightly different process: the process of building an entirely new market that then replaces older ones.

- Again, just to be clear, the situation in the old town is not primarily due to the direct effects of disruptive technologies, even though mass internet surveillance, drones and other—lets say by-now traditional—means of warfare are of course utilized.

- The term “mob” derives from “mobile vulgus” or “fickle crowd.”

- Jean-François Lyotard, ‘The Sublime and the Avant-Garde’, in The Inhuman (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991).

- Ibid., Hallward; Ibid., Jameson.